Adler’s & Jung’s Insights for Artistically Creating Your Life: Part 1

© 2025 Bonnett Chandler, MA, LPCC, Richard Chandler, MA, LPC, Kelly Krueger, MA, LMFT

In May of 2016 I presented Adler's & Jung's Insights for Artistically Creating Your Life to the 64th annual conference of the North American Society of Adlerian

Psychology (NASAP) in Bloomington, MN.

Abstract

This paper applies Alfred Adler’s and Carl Jung’s psychological principles to the question of creating our lives in an intentional and artistic way.

Although there is a body of psychological writings comparing the principles of Alfred Adler to those of Sigmund Freud, and even more writings comparing Carl Jung’s constructs with those of Freud’s writings that compare and contrast Alfred Adler’s body of work to that of Carl Jung’s, are limited. This paper presents affinities, comparisons, contrasts and an integration of Adler’s and Jung’s insights for the purpose of supporting artistic creation and self-actualization.

What Motivated This Choice Of Topic?

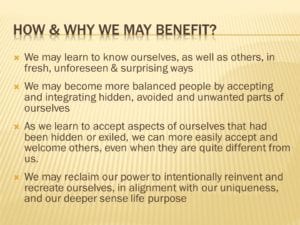

Although much of psychology focuses on dysfunctions in mental health, this writer was curious to discover how people without mental health impairments might utilize the psychological principles of Alfred Adler and Carl Jung to artistically create their lives.

The word “artistically” implies:

- Movement inward, by journeying deeply into our interior psyche.

- Movement outward, by retrieving and transforming our inner discoveries into creations of value, to be shared with others.

- Aesthetics, by creating our lives as works of art, so our individually unique vision of truth and beauty concurrently embraces principles of universality, and therefore connects with our mutual humanity.

- Intentionality, by embracing our responsibility for uniquely creating our lives.

- Action, which is the indispensable ingredient for creating.

Why Alfred Adler’s And Carl Jung’s Insights Inform Artistic Creation Of Our Lives?

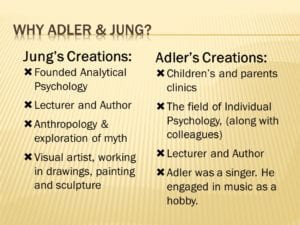

In addition to acknowledging the artistic creation shown within their published writings, Adler and Jung personified artistry and creation within their lives. In addition to his life as a psychologist, author, lecturer and the inventor of “Depth Psychology,” Carl Jung lived the life of a visual artist, working in drawing, in painting, and in sculpture mediums (Shamadasani, 2009). Adler also led an artistic life, taking the lead in creating – along with collaboration with his colleagues – the field of “Individual Psychology” (Hoffman, 1994). Along with his associates, he also created a network of children and parents’ clinics in Germany (Hoffman, 1994). Additionally, Adler was a singer and engaged in music as a hobby (Bottome, 1957).

Alfred Adler’s Insights for Artistically Creating Our Lives

Inferiority, Superiority And Assigned Meaning

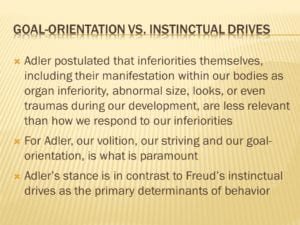

Alfred Adler (1917) postulated that inferiorities themselves, including their manifestation within our bodies as organ inferiority, abnormal size, looks, or even traumas during our development, are less relevant to living fulfilling lives, than how we respond to our inferiorities (Adler, 1917). For Adler, our volition, our striving and our goal-orientation are paramount. His position sharply contrasted with that of Sigmund Freud, who posited that instinctual drives are the primary motivational determinants of human behavior. Adlerian authors Oberst and Stewart (2003) write:

But in spite of the mutual respect the two men had for each other, a certain rivalry between Freud and Adler existed from the inception of their relationship. It seems that Adler never was wholly convinced of all of Freud’s ideas, especially the concept of sexuality being the primary motivator of most behavior. (Oberst & Stewart. 2003, p. 3)

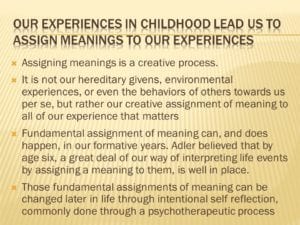

In Alfred Adler’s view (1992), we assign meanings to our experiences, from very early childhood onward. Meanings assignment is a creative process that serves to either empower or disempower us, either connecting us more deeply and empathetically with our fellow humans, or to instead motivate us to cut our ties to others, or even to seek power over them. The meanings that we assign become a filter from which we view all of our new experiences, often reinforcing earlier assignments of meaning. Adler taught that it is not our hereditary givens, environmental experiences, or even the behaviors of others towards us per se, but rather our creative assignment of meaning to all of our experience that matters most (Adler, 1992). He also believed that our foundational assignment of meanings occurs in our formative years. But meaning can be changed later in our lives through an impact of a major life event, or due to intentional self-reflection, commonly occurring within a psychotherapeutic process.

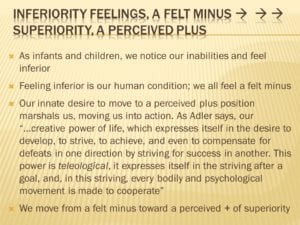

As infants and children, we notice our inabilities and feel inferior to older siblings and adults. Feeling inferior is our human condition; we have all felt, and will continue to feel a “Felt Minus” from time to time. Our innate desire to move to a plus position marshals us. A healthy response is to move forward through actions that give us more of what we want, and away from feelings of inferiority. Alfred Adler writes:

Our …creative power of life, which expresses itself in the desire to develop, to strive, to achieve, and even to compensate for defeats in one direction by striving for success in another. This power is teleological; it expresses itself in the striving after a goal, and, in this striving, every bodily and psychological movement is made to cooperate. (Ansbacher & Ansbacher, 1956, p. 92).

Thus we move from a “Felt Minus” toward a “Perceived Plus” of superiority, which is a healthy human response.

There Are Three Common Ways That Healthy Striving Towards Superiority Might Be Derailed:

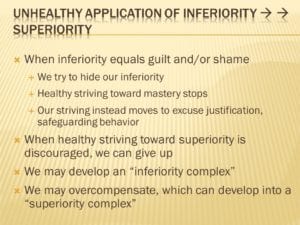

- When inferiority equals guilt or shame, we might attempt to hide our inferiority. When this occurs, healthy striving toward mastery stops and our striving response instead might become a quest for reasonable excuses as a justification for our perception of inferiority.

- When healthy striving toward superiority is discouraged, we can give up, which often leads to avoiding situations, or people, that remind us of our inferiorities.

- We may overcompensate, which can develop into a “Superiority Complex,” as described by Alfred Adler:

The superiority complex, as I have described it, appears usually clearly characterized in the bearing, the character traits, and the opinion of one’s own superhuman gifts and capacities. It can also become visible in the exaggerated demands one makes on oneself and on other persons (Ansbacher & Ansbacher, 1956, p. 261).

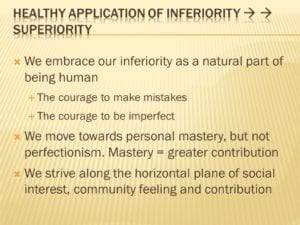

In Adlerian “Individual Psychology” we accept our inferiority as a natural part of being human. In doing so, we embrace two stances that are vital for artistically creating our lives, which Adlerian practitioners are fond of stating. These stances are: “the courage to make mistakes” and “the courage to be imperfect.” Without committing to these stances, our creative striving forfeits to the fear of our own judgments, or the judgments of others, and forfeits to the fear of making mistakes and not arriving at an ideal conclusion in our initial attempts to create. Much of the process of authentic creation involves outwardly creating our inner vision, even though there are no guarantees that our creative work will be met with acceptance. In addition, a great deal of the creative process is one of trial and error as we make multiple attempts to create, followed by the typical realization that we have created something that clearly fails to have a result that we wanted, and a result that others are able to accept as artistically competent.

But in those multiple, imperfect attempts, we learn through our efforts to create something new. We also learn from our creations themselves, as they give us real-world feedback as to what has and has not worked. Through years of attempting, and the feedback that our imperfect creations have provided for us, we move towards personal mastery. It is imperative that we make a critical delineation here, noting that personal mastery is not perfectionism. Moving towards mastery is not done to be better than others, or to achieve perfection; personal mastery is in service to making greater contributions to our fellow humans.

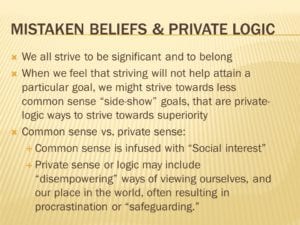

Common Sense Vs. Private Sense

Adlerian psychology contends that our deepest need as humans is to belong and to be significant (Oberst & Stewart, 2003). Adler describes our healthy impetus of moving towards superiority, infused with “Social Interest” and “Community Feeling,” which are “Common Sense” ways of contributing. Unlike socially recognized common sense, “Private Sense,” or “Private Logic” along with “Mistaken Beliefs, consists of disempowering ways of viewing ourselves, of viewing others, and of reconciling our place in the world, which might result in procrastination or “Safeguarding” behavior. This can occur should we become discouraged in our striving towards goals in the arenas of work, close relationships or community relationships, placing us instead at risk to strive in less common sense ways, choosing to embrace “side-show” goals, also known as a private logic ways of striving towards superiority (Oberst & Stewart, 2003).

Common sense ways of artistically creating our lives results from examining our own private logic, and mistaken beliefs, so that we may decide whether or not those beliefs are empowering or disempowering. Adlerians do this through a process of recalling our “Early Recollections” or ER’s, in which we recollect memories from the early part of our life. By remembering a specific event or story from our earlier life, we discover a direct pathway into our less-conscious ways of thinking, believing and striving. Examples of disempowering private logic, which may be discoverable through “early recollection” inroads into our unconscious, might include internal messages of not being talented, smart or creative. Through ER’s, we discover insights into our patterns of getting stuck, thus allowing us to make course corrections and restore healthy forward movement towards our common sense goals (H. H. Mosak & R. D. Pietro, 2006).

Perfectionism

A private logic mistaken goal, frequently experienced by many, is perfectionism. The voice of perfectionism speaks in the dialect of mistaken beliefs. For both artists who create, and for performance artists, including musicians, dancers and actors, the voice of perfectionism might say:

- “If my stage performance isn’t perfect, it’s not good at all.”

- “If I’m not perfect, people will judge me harshly.”

- “If I can’t do it perfectly, I shouldn’t even try.”

- “I expect that others will have the same standards as me.”

Perfectionistic ways of believing has disempowering relatives. They include:

- Anxiety, depression and self-image distortions

- Loss of confidence

- Procrastination

- Fear of failure

- Unwillingness to risk

- Despair

Perfectionism’s Antidotes Of Adopting Realistic Standards And Horizontal Striving

One antidote to perfectionism is to externalize it. This author suggests calling it: “The voice of perfectionism, who speaks in the dialect of mistaken beliefs.” This voice tries to convince us that we should not even try to artistically create our lives, as we don’t have what it takes to do it perfectly. This statement is an example of a mistaken belief, because we know that even if we do not achieve some unattainable perfection, we still will create our lives in more optimal ways than would be the case if we had heeded this voice and not even tried. Adlerians like to tell themselves and others that they will just “take a whack at it.” When concerned over whether or not their creation, or their performance, was stellar in every way, Adlerians tell themselves that it was “good enough.” We would do well to recall humorist and politician Al Franken’s fictitious character, Stuart Smalley, who self-soothed by saying: “I’m good enough. I’m smart enough. And doggone it, people like me.” (Franken, 1991)

An Adlerian construct that is particularly helpful for performance artists, as well as anyone who feels exposed when in front of others, is the “Vertical Plane of Striving vs. the Horizontal Plane of Social Interest and Community Feeling.” When people strive vertically, it is as if they live their lives on a skyscraper’s elevator, and are constantly monitoring who is living a higher floor and who they have risen above. When their performance goes well, it is if as if they have ascended several floors and can look down on even more people; but when their performance isn’t as good, their elevator descends to a lower floor of diminished status.

Vertical striving places too much focus on us. We might compensate by:

- Comparing, judging and criticizing.

- Occupying ourselves by deciding who we are better than, or not as good as.

- Believing that others are judging us, because after all, we are judging ourselves.

Horizontal striving, in contrast, confirms that we are all in this together, audience and presenter or performers alike. We believe that the audience is cheering on the presenter or performers, due to inherent human empathy. Because the audience, presenter or performer, and even behind-the-scenes stage people, all are co-creators of an event, everyone present desires the best possible experience and outcome for the performance. Therefore, if we are in the role of performer or presenter, we can afford to relax and let go; positive support is ever present.

The Creative Self

The final Adlerian concept that informs how we may artistically create our lives is “The Creative Self.” Alfred Adler believed that our inherent makeup, in terms of the ways in which we create our lives, is artistic. In other words, like artists, composers, inventors or entrepreneurs, we create our lives as our own, unique works of art. It is our creative volition that determines what we strive for in life. Adler (1956) said: “The individual is thus both the picture and the artist” (p. 177).

Carl Jung’s Concepts Inform Artistic Creation

The Personal And The Collective Unconscious

The “Personal Unconscious” informs us on what may have gone unnoticed in our lives. It our personal repository for original ideas, felt emotions, images, soundscapes and improvisational kinesthetic impulses. All of these, and many more, are our foundational building blocks, the source material for what we create. What truly wants to come through for uniquely creating our own way, which Jungian Galen Martini (2006) describe as the process of “Individuation,” arises from our personal unconscious via our dreams, the symbols that we are attracted to, or even through synchronous events that we both notice and mine as a source of artistic insight (Martini, 2006).

The discovery of the “Collective Unconscious” is primarily credited to Carl Jung (Shamadasani, 2009). As we travel inward, into the deepest regions of our personal unconscious, we leave our personal references behind and have traveled into a vast repository of images, symbols, stories and myths that are common to all of us as humans. The collective unconscious connects us with all of humanity, across culture, ethnicity, geographic distance and even time.

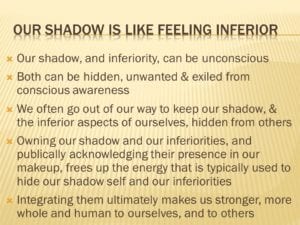

Jungian’s believe that when our shadow self remains hidden from our conscious awareness, it can powerfully influence our thoughts and behavior in ways that undermine ego-control of our lives and lead to destructive ways of thinking and behaving. Confronted by our shadow, we commonly respond by ignoring it, denying it, or distancing ourselves from uncomfortable or even painful awareness of our shadow self.

To more successfully create our lives in an artistic way we need to do the opposite; we must welcome and except those unwanted aspects of our “Self” into conscious awareness. Paradoxically, by doing so, those previously exiled shadow aspects of our “Self” may be reincorporated into the totality of our conscious awareness, and therefore those shadow aspects’ capacity to negatively impact our lives is to a large extent mitigated, for they no longer operate as a shadow government, controlling the operations of our lives without the conscious permission of our ego (personal communication, August, 2014). For those latent shadow aspects, rich with artistic potential, the act of welcoming and embracing our shadow might prove to be fruitful and rewarding as we artistically create our lives.

In illuminating Carl Jung’s understanding of the relationship between the personal and collective unconscious, author Sonu Shamadasani (2009) writes:

[Jung] … differentiated two layers of the unconscious. The first, the personal unconscious, consisted in elements acquired during one’s lifetime, together with elements that could equally well be conscious. The second was the impersonal unconscious or collective psyche. While consciousness and the personal unconscious were developed and acquired in the course of one’s lifetime, the collective psyche was inherited. … [Jung] discussed the curious phenomena that resulted from assimilating the unconscious. He noted that when an individual annexed the contents of the collective psyche and regarded them as personal attributes, they experienced extreme states of superiority and inferiority. He borrowed the term godliness from Goethe and Alfred Adler to characterize the state, which arose from fusing the personal and collective psyche, and was one of the dangers of analysis. (S. Shamadasani, 2009, p. 208)

Psychological Personality Types

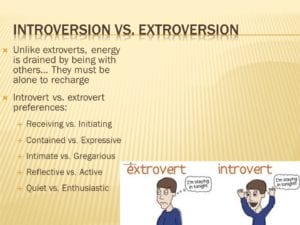

Carl Jung was the first to write about our innate psychological personality preferences, or psychological types (Jung, 1971). The overall polarities that he established include:

- Introversion vs. extroversion

- Sensing vs. intuiting

- Thinking vs. feeling

- Perceiving vs. judging, or decision-making

All of these polarities may be measured by taking the Myers-Briggs® assessments, which are based in large part upon Jung’s constructs. It is this writer’s belief that people may gain advantageous insights into themselves and others, by taking and receiving an interpretation from an experienced Myers-Briggs practitioner of the MBTI® Step II psychometric instrument, which subdivides each of the above polarities into five sub-processes (K. D. Myers & P. B. Meyers, 2001, 2003). Although the simplistic Myers-Briggs instrument is helpful, the additional precision and clarity gained through the MBTI® Step II instrument and interpretation is superior for understanding how to artistically create the life that we aspire to.

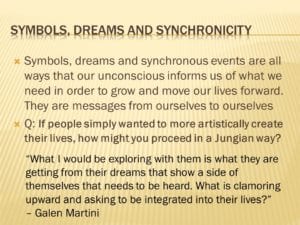

Symbols, Dreams And Synchronicity

The landscape of our personal and collective unconsciousness is largely made up of symbols, dreams and the common experience of synchronicity. Paying attention to the symbols that we are drawn to, or repelled by, in our waking life, as well as the symbolic meaning of our dreams, illuminates the meaning we assign to our lives. This rich reservoir from our unconscious informs us of what we need to consider in order to grow and to move our lives forward. Our unconscious symbols, dreams and synchronous events are messages from ourselves, to ourselves (Martini, 2011).

The “Anima” And The “Animus”

Like Alfred Adler, who talked about the role of gender guiding-lines as an aspect of our “Style of Life,” Carl Jung wrote about the influence of masculine and feminine energies within the totality of our self, which he identified as the “Anima” and the “Animus.” Artistically creating our lives may be informed by considering the ways in which “Yin” or female energies, and “Yang,” or male energies, consciously and unconsciously influence us. Artistic creation may be enhanced by choosing to include more yin energy, so our creations may be fluid and flowing. In contrast we might find greater benefit by incorporating more yang energy, instead emphasizing structure and more defined boundaries, in order to achieve the life that we want. Men may particularly find balance by consciously embracing the female energy of the anima, while women often achieve greater balance by embracing their inner animus, their masculine energy (Millner, 2004).

Archetypes

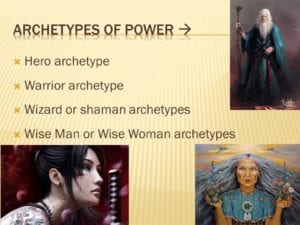

Through insights gained from his lifelong interest in stories, fairytales, myths and the metaphysical beliefs of other cultures, as well as from his own personal journey into the collective unconscious, Carl Jung wrote about archetypal life patterns (Jung, 1964). Those that most directly apply to artistically creating our lives revolve around archetypes of personal power, wisdom and the act of creating itself. Creation-oriented archetypes include:

- The “Hero”

- The “Warrior”

- The “Wizard” or “Sorcerer”

- The “Shaman”

- The “Wise Man” or “Wise Woman”

- The “Artist”

- The “Muse”

- The “Musician”

For most people, archetypes operate unconsciously, emanating as they do from the realm of the collective unconscious. By bringing our archetypal influences into conscious awareness, we have the opportunity to examine the extent to which they empower or disempower us. In many ways, artistic archetypes have chosen us. By acknowledging those patterns that do hold sway over our lives, and consciously choosing the archetypes that best support our aspirations, we may enlist our mix of archetypes as allies in our quest to artistically create our lives.

The “Self” And The “Shadow Self”

In Carl Jung’s mapping out of the psyche, we find both the conscious and unconscious construct of the “Self,” which, in part, includes:

- Our persona, which is the aspect of our identity that we are comfortable sharing with others.

- Our ego consciousness, the aspect that we relate to as our conscious inner “I.”

- Our shadow self, which operates both within our conscious awareness and below it, in the realm of our personal unconscious. (Millner, 2004).

Our shadow self contains thoughts, feelings, desires and biases that may be embarrassing, shameful or even abhorrent to us, and also perhaps to others. It may also contain latent aptitudes and artistic sensibilities that yet remain unexplored (Jung, 1964).

How might we explore our shadow selves? For the more troubling aspects of our shadow, Jungian’s have recommended that we begin by noticing what really bothers us in other people, paying special attention to those words, beliefs or actions of others that precede a strong emotional reaction from us, as this is a major clue that we too house similar thoughts, beliefs or propensities within our own psyches.

Our dreams may also inform us of those latent, unexplored parts of ourselves. While interviewing Jungian Analyst Galen Martini, I asked: “If people simply wanted to more artistically create their lives, how might you proceed in a Jungian way?” She responded: “What I would be exploring with them is what they are getting from their dreams that show a side of themselves that needs to be heard. What is clamoring upward and asking to be integrated into their lives” (G. Martini, personal communication, August 28, 2014). This is the key to working with our shadow selves; reintegration of our shadow into conscious awareness brings wholeness to our lives, allowing us to transcend and overcome the paralysis of a fragmented self. Instead of vilifying our shadow, we out it!

Life Cycles

Carl Jung addressed the cyclic nature of our lives, from the early acquisition of knowledge and experience, to our rising competence in our 20s and 30s, to the disruptive falling apart that so often occurs in midlife and through a reintegration towards a more holistic expression that may best describe our later years. Artistic creation frequently requires that something die in order for something new to be born (Millner, 2004).

As people have the courage to allow many aspects of their earlier adult life to die, there seems to be a kind of rebirth that occurs, a re-animation of their life by a self that had been largely ignored, a self that might remind a person more of how they were in their teenage years, in terms of being more optimistic and confident about life’s possibilities, their possibilities. (Chandler, 2013, p. 4)

Individuation

Jungians believe that all healthy people go through a process of individuation; we grow by breaking away from the life prescriptions written for us by our families of origin. To artistically create our lives, or to actually become an artist, an even greater degree of individuation often occurs as an expression of finding one’s own way, both in living life and through acts of creating. Galen Martini (2006) states:

By tapping your unconscious strengths and uncovering repetitious, negative or self-defeating patterns you can find and reclaim your life. … With reflection, you can move out of old worn out attitudes, “the old house” of self-sabotaging beliefs that you designed and inhabited to protect yourself at an earlier time, and into the house of yourself.” (Galen Martini, 2006, p. 27)

The Jungian-informed Technique Of Drawing With The Non-dominant Hand

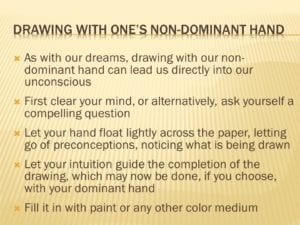

In much the same way that recurring symbols, the content of our dreams, and insights from synchronous events reveal meaningful content from the unconscious, drawing with our non-dominant hand opens our unconscious world to conscious reflection by intentionally journeying inward.

Galen Martini (2014) provides the steps for drawing with our non-dominant hand:

- First clear your mind, or alternatively, ask yourself a compelling question.

- With pencil in hand, let your hand float lightly across your paper, letting go of preconceptions.

- Without interference from your conscious awareness, simply allow your hand to draw what it will, noticing what is being drawn.

- Let your intuition guide the completion of the drawing, which may now be done, if you choose, with your dominant hand.

- Fill the pencil drawing in with paint, or any other color medium that the drawing seems to call for.

During the process of making the drawing, or upon reflection after its completion, your creation is likely to have a specific insight for you. This technique may be especially useful when facing some uncertainty about how best to proceed forward in your life. (Martini, personal communication, September 5, 2014)

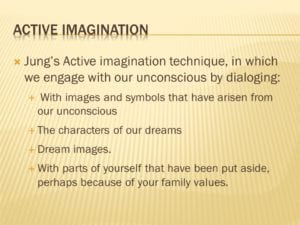

Active Imagination

Jung taught and used the technique, “Active Imagination,” in which we dialog with images from our unconscious, or with our dream characters. These could include parts of yourself that had been put away, perhaps because of your family’s values. In her second interview with this writer, Galen Martini (2014) stated:

After many years of conceptual work, I still needed to write my thesis, and I was very tired. I needed the energy of my intuitive self, my right brain side, to balance out from all of the left brain work, so I could actually write. Using Active Imagination while drawing with my non-dominant hand, a muse showed up, admonishing me to paint as a way to have energy to write my Jungian thesis. It showed up spontaneously on the page much like a dream and gave me access to that artistic side of myself that I’d had to put aside doing years of rigorous Jungian conceptual study. I really listened to it too, and wrote all morning and painted from the unconscious each afternoon, and finished my thesis this way. (Martini, personal communication, September 5, 2014)